Do you have a grandmother who always knows the perfect cleaning product for just about anything? Mine certainly does, and those childhood memories found their way into my career – in my work as a conservation specialist I often think about how to clean different objects and why certain methods work best.

Dirt layers are a complex mixture

It’s a fascinating area of research as every artwork is different, both in terms of its materials and the way it ages. In conservation, removing dirt from the surface of an artwork is known as superficial cleaning. This protects the piece from further damage and also makes it look better. Let’s dive into the history of this cleaning method and how we use it today in our conservation studio, using the restoration of A Portrait of Marianne Theresia Brockhaus (1913) by William Valentine Schevill (1864-1951) as an example. Dirt layers are a complex mixture of organic and inorganic compounds from dust, pollution, nicotine, cooking residues like fats and oils, insect droppings, etc. Over time, these layers build up, darken the surface of the work and reduce the vibrancy of colours and contrasts.

Theodore de Mayerne's recommandation

Throughout history, different techniques were developed to remove these layers of dirt. For example, in his 17th-century manuscript, Theodore de Mayerne (1573-1655) recommends using bread to clean paintings. Other unconventional materials, such as onions or potatoes, were also used in the past. With industrialisation, new products were commercialised and scientific research into restoration expanded. By the late 20th century, chemists had developed detailed methods for cleaning paintings which were tailored to the specific characteristics of each painting and the particular challenges it presented instead of using a one-size-fits-all approach. This has led to more effective and controlled restoration practices over time.

A one-size-fits-all approach

Throughout history, different techniques were developed to remove these layers of dirt. For example, in his 17th-century manuscript, Theodore de Mayerne (1573-1655) recommends using bread to clean paintings. Other unconventional materials, such as onions or potatoes, were also used in the past. With industrialisation, new products were commercialised and scientific research into restoration expanded. By the late 20th century, chemists had developed detailed methods for cleaning paintings which were tailored to the specific characteristics of each painting and the particular challenges it presented instead of using a one-size-fits-all approach. This has led to more effective and controlled restoration practices over time.

A risky business

One of the main objectives of restoration is to understand and control our interventions in order to protect original materials and ensure their long-term preservation. This principle also applies to superficial cleaning, where the products used must not alter the artwork’s original components. Water is often used to dissolve surface grime and might seem like a simple, harmless solution. However, despite being non-toxic, H₂O is a powerful molecule that can pose significant risks.

As we know from chemistry, water can act as a physical solvent, dissolving hydrophilic materials, and cause chemical reactions based on its pH – an indicator of acidity or alkalinity. Controlling pH is therefore essential, as it interacts with the chemical nature of the original material and can potentially damage it. Other factors such as conductivity, diffusion, and evaporation time are also carefully considered during the cleaning process. By understanding these complexities, we can tailor our solutions to the specific situation and use them in a controlled and intentional manner. As we’ll see in the next section, understanding the painting and its materials is also crucial.

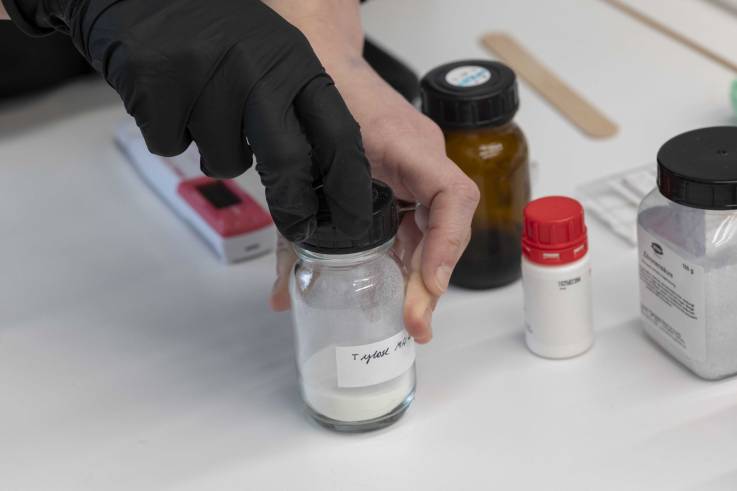

Where the magic happens

The Portrait of Marianne Theresia Brockhaus arrived at the studio for superficial cleaning. This oil painting on canvas features an original varnish layer. Prior to treatment, we anticipated potential sensitivities due to the worn condition of the varnish, which no longer served as an effective barrier. As a result, our cleaning solution could come into direct contact with the paint layer, making precise control essential. Indeed, the water could react with the oil binder because of its acidity and dissolve water-sensitive additives known to be part of modern oil formulations.

First, we adjusted the pH of the solution to stay within a safe range for oil-based binders, ensuring both pH and conductivity were suitable. We also buffered the water – meaning its pH would stay the same throughout the cleaning process –, providing a controlled chemical environment. The treatment‘s effectiveness was improved by adding a weak chelating agent which targeted the grime on the surface of the painting. This molecule has a special structure with “arms” that can attach to metal ions found in dirt particles. Next, we chose an application method using absorbent papers, which prevented the solution from spreading into the paint layer or the cotton canvas and minimised abrasion on the delicate surface. As a result, the portrait regained its vibrancy, and the painting was preserved thanks to a tailored treatment that respected its unique features.

Text: Laura Guilluy - Photos: Éric Chenal

Source: MuseoMag N° III - 2025