Inside the studio of Letizia Romanini, the Luxembourg-based artist on display in our Beyond The Frame exhibition

I meet Letizia Romanini in her new studio in Bonnevoie. The space still has that just-moved-in feel; a few things are still wrapped up, some boxes waiting to be unpacked. After more than two decades in Strasbourg, the artist has recently moved back to Luxembourg. “I needed to change my surroundings,” she says. “To close a chapter that was tied to my studies. I felt like I’d done everything I needed to do in Strasbourg.” With four of her works featured in our current exhibition Beyond The Frame. Rethinking Photography and the museum having acquired two of her sculptures last year, it felt like the right moment for a long overdue studio visit to discuss her artistic practice in person.

Reconnecting past and present

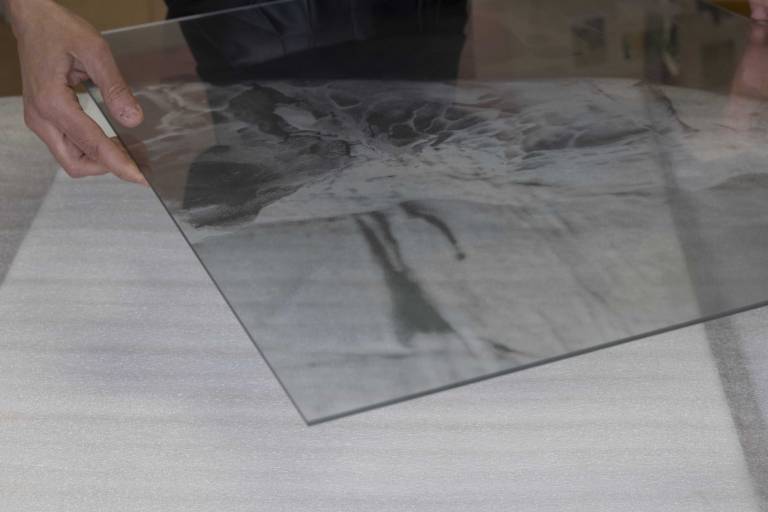

Romanini’s work often centres on themes of memory, place and observation; ideas that are closely tied to both her upbringing in Luxembourg and her Italian roots. The pieces she’s showing as part of this year’s EMOP exhibition at the museum explore the same themes. At first glance, the shapes appear quite abstract, but on closer inspection, it becomes clear that they are in fact photographs, based on the artist’s own images and printed as serigraphs using reflective ink on glass. Two of these images were taken during the artist‘s Tour de Luxembourg, a 24-day walk she embarked on in August 2021, tracing the borders of the country. “Everyone says Luxembourg is so small that you know every bit of it,” she explains, “but in reality, when you live there you often go back to the same places.” The walk became a way of reconnecting with her home country, but also seeing it differently and paying closer attention to things that usually go unnoticed.

The other two works in the series, also featured in the exhibition, draw on the artist’s Italian heritage, specifically the Frasassi Caves in Marche, the region her grandparents lived before moving to Luxembourg. “In the Marche region where they come from, these amazing Frasassi Caves were discovered in 1971, which completely changed the region. Suddenly there was tourism. I wanted to echo that economic history. Just as the steel industry shaped Luxembourg, the caves shaped that part of Italy.” She unwraps more pieces from the series in the studio, and as the light hits the mirrored surfaces, it’s easy to see how the title The Oath of Impermanence perfectly captures the essence of the work. “You see yourself in it,” she says. “The idea is that these stalactites, stalagmites, the rock and the mud, they’ve taken millennia to form. Nothing is permanent, least of all us. Compared to these elements that have taken so long to form, our lives are fleeting. I think there’s a sense of vanity in that too: when the viewer looks at the piece, they are someone, but two minutes later they’ve already changed, they’ve become someone else.”

Preserving the ordinary

The idea of impermanence also ties into a broader theme in Romanini’s work; finding meaning in the everyday and the ordinary, a theme that’s has been central to her practice from the very beginning. She points to a small, dark wooden shelf on the wall, which holds a collection of bronze trinkets. At first glance, these tiny objects almost look like jewellery. A fitting observation, considering that the artist also creates jewellery, sometimes even incorporating it into her photography. She tells me that this work is one of her earliest pieces, made during her first residency in Berlin in 2008. “I set myself a rule: everything I collected had to fit in the palm of my hand,” she recalls. “In Luxembourg or Strasbourg, I didn’t find many discarded objects like that, but in Berlin, the streets were full of them.” So she began collecting fragments from the city, a process that still influences her work today.

The bronze objects we then continue to unpack and take a closer look at, made during the Tour de Luxembourg, were also collected along the way. In these works, the everyday is transformed into something entirely new, with simple items becoming lasting works of art. “I really wanted to stay true to the themes and ideas that have been present in my work since leaving art school, things to do with the everyday, the mundane, the unspectacular. I wanted to show a certain materiality of the real and play with materials to make them more sculptural,” Romanini explains.

As she unwraps the pieces, it’s striking how even the most ordinary, sometimes even random objects, take on a completely new meaning through this artistic process. “This was a scrunchie,” she laughs, holding up a roundish bronze object that now looks more like a clump of ploughed soil. Once soft and fluffy, it’s been transformed into something solid and lasting: “Now, it’s something else entirely. It’s about playing with time and giving new life to things that were once fleeting.” She then shows me a delicate thorn, whose fragile form looks surprisingly robust in bronze. “It’s so fragile, and that’s what I love,” she says. “If someone stepped on it, or even an animal, it would’ve been crushed. But now, frozen in time, it holds its shape forever.” Last year, the museum acquired Robinia 1 and 6, two bronze branches of black locust Romanini came across during her walk along the borders of Luxembourg.

Reviving old crafts

Continuing with the idea of connecting past and present, we turn to another series in the artist’s practice: her straw marquetry works. One of the pieces from this collection hangs in the studio, its surface consisting of organic shapes in earthy tones that, despite their abstract nature, create a sense of depth, almost like a landscape painting. She brings out boxes of dyed straw and the small wooden tools used to flatten and press them into place, showing me how this centuries-old technique works. It’s slow and detailed, and for her, that’s exactly the appeal. “I wanted to learn new techniques,” she says. “And often, I’m interested in things that link me to the past, or to a kind of knowledge rooted in crafts. Like ceramics, or techniques that work with metal, or those linked to straw marquetry, a craft which dates to the 17th century. And through learning these practices, I feel like I’m carrying them from a certain past into a certain future.”

Funnily enough, she first came across straw marquetry quite unexpectedly, through a TV feature she happened to catch while visiting her parents. “Right away I thought this is magic! It’s beautiful, it’s slow, it’s meditative, it’s meticulous, it’s repetitive, it’s everything I love.” But it wasn’t until she began the Tour de Luxembourg that using the technique really made sense to her. Passing through field after field of straw, the rhythm of the craft began to mirror the act of walking. “There’s something slow about it,” she says. “The image builds up stalk by stalk, just as I crossed the landscape step by step.”

As I watch her carefully split the straw, accompanied by an almost meditative crackling sound, Romanini tells me how excited she was when the museum approached her to lead a workshop as part of the upcoming Land in Motion. Transforming People and Landscapes programme: “I’m interested in the idea of sharing, of passing on to others what I’ve learned.” Hearing this, I can’t help but think about the theme that runs through her work; connecting past and present, people and elements of nature. In the end, it’s about communicating these ideas through her practice: “I see myself as someone who translates what’s around me, not just for myself. Sure, it’s satisfying, I love creating, being in the studio, I need that bubble. But if I can’t communicate with the outside world, if it’s just for me, then it loses all meaning.”

Text: Lis Hausemer / Images: Eric Chenal

Source: MuseoMag N° III - 2025

Romanini’s works are on display in the exhibition Beyond The Frame. Rethinking Photography at the Nationalmusée um Fëschmaart until 16 November 2025. Free entry.